What Nature Can Teach Us About Notifications

Emmi Laakso, Former Senior Product Designer

Article Category:

Posted on

Notifications feel like a necessary evil; they keep us informed, but also distract, stress, and otherwise negatively affect our lives. So, what exactly is the problem? And how might we make it better? Here are a few theories.

Outside of speech, humans have relied on notifications for almost as long as we’ve been human; a dog’s bark to warn us when something was lurking beyond the reach of our campfires, a rooster’s crow to mark the morning. Inevitably, we developed technology for that purpose. The first bells, dating back to about 1000 BCE in China, were used for communication over long distances and as time progressed, we started using notifications to call people to religious observance, to warn of danger, and mark time.

As our technology has matured, the form that notifications take and what they stand for has continued to evolve. Fast forward to 2018, and we receive much more information than our ancestors probably could have imagined. It seems like everything we surround ourselves with talks to us via notification, and that pervasiveness has had an impact on our lives. From statistics around distracted driving contributing to 9 deaths everyday in the US, to studies showing how notifications negatively affect our ability to perform tasks and remember information, cause stress, and make us unhappier, it’s clear that how our current systems handle notifications is broken.

So, what exactly is the problem? And how do we make it better? Here are a few theories.

Notifications are ambiguous.

Recommendation: Focus on people, not apps.

“Originally all sounds were originals… sounds were then indissolubly tied to the mechanisms that produced them.”

Murray R. Schafer

Your brain is capable of tuning out an incredible amount of signal. When you’re walking in the woods and your ears pick up the sound of running water, you may not actually hear the sound until you’re listening for it or the sound is loud or novel enough to cross a perception threshold. That’s because the signal (the sound of water) is a sound you’ve heard before and specific enough for your brain to identify and dismiss without conscious thought.

When a ding ding rings across any contemporary room, the result is universal; everyone feels the need to check their phones. Even if we're alone in a room, the compulsion is hard to ignore. Studies have shown that when a mobile notification arrives, our bodies release a stress hormone called cortisol. That mini fight-or-flight response then persists, sometimes for minutes, until we check the notification. If our brains are capable of tuning out most signals, why can’t we tune out notifications? According to Tristan Harris, a start-up founder and former Google engineer, it's because when it comes to notifications, our phones act a little bit like mini slot machines. Meaningful information mixed with false positives create intermittent positive reinforcement, and because everything more or less behaves and sounds the same, there's no way to tell what kind of information is coming our way. That ambiguity is stressful. As a result we lose focus, and check our phones.

“If [a sound’s] qualities are ambiguous, we become uneasy and uncomfortable. In order to identify distracting or confusing elements in our perceptual realms, we need to focus on them.”

Michael Stocker

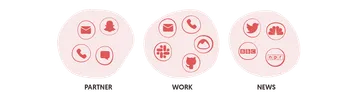

So how can notifications become less ambiguous? One possibility is to associate notifications with meaningful entities, like people, rather than apps. An entity could be a single important person (your partner), a group of people who all generally contact you for a particular reason (your coworkers), or even a group of apps that pertain to a specific subject (recent news).

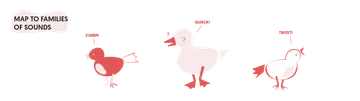

Then, distinct entities could each be mapped to specific types of sounds or signals (think different types of bird songs, for example), to help you identify the type of notification you're getting, and by proxy help reduce the cognitive stress of ambiguity and break the cycle of intermittent positive reinforcement.

Notifications lack hierarchy.

Recommendation: Create natural hierarchy with proximity.

In nature signals have inherent hierarchy created by physical proximity. Something that you see in the distance, like a bee, is less alarming than if that bee flies closer and you can hear it buzzing directly next to your ear. And if that bee comes even closer to you and lands on you, or even stings you, feeling the bee is even more alarming than the sound of buzzing. In this way, sight, sound, touch and pain provide a natural hierarchy of notification.

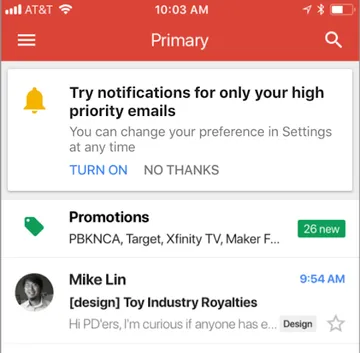

When we receive notifications on our connected devices, by contrast, there is very little hierarchy of signal. Although visual banners and sounds and the sensation of tapping are all possible with mobile and wearable devices, most notification systems don’t even attempt to facilitate the creation of hierarchy, let alone do it automatically. The closest that current system notifications come to this idea is probably in Gmail for iOS, which this year introduced the ability to only turn on notifications for priority email. Although this new feature creates some level of hierarchy, it doesn’t make use of different signals, just removes certain notifications entirely based on what the service perceives to be important.

Imagine if signals for notifications varied from ambient to distinct, loud to soft, bright to muted, light to heavy, warm to cold. Creating a range of signal, paired with the natural hierarchy of our senses could help us parse important notifications from fluff.

Notifications lack context.

Recommendation: Create systems that help people communicate context and importance.

In physical spaces it is impossible to ignore the role of context in helping to create meaning from signals. The sound of running water means something very different in the woods than it does in a bathroom, and because the sound is expected in those spaces it isn’t disruptive to anyone else.

Mobile notifications, on the other hand, exist entirely independently of context and, as the marimba ringtone that famously disrupted the New York Philharmonic concert demonstrates, open up the possibility to receiving notifications that are not just personally stressful, but socially inappropriate. The stress of context conflict is cited as the reason why most people turn off their notifications altogether, or activate Do Not Disturb in socially sensitive situations. And although receiving no notifications seems to be the best solution right now, it contributes to another type of stress; the fear of missing something important.

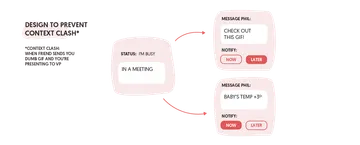

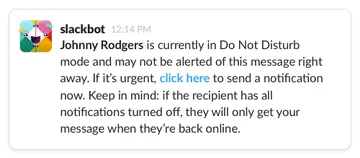

So how can technology mind context? Notifications may never be able to discern context intelligently, because context goes way beyond your location to your activity, intent, and priority. The answer may instead be to provide better tools to senders and recipients of messages to help facilitate conflicts of context. Slack’s Do Not Disturb feature is a great example of a smarter notification tool; not only can people provide a status and set hours for Do No Disturb, but their coworkers can see that status, and flag a message as urgent and trigger a notification anyway. By giving both parties agency and relevant information, this feature uses people’s ability to interpret urgency and context so that technology doesn’t have to.

Another, arguably even simpler way for technology to mind context is to just make it less complicated to change notification settings on the fly. Imagine being able to adjust which people can break through your Do No Disturb immediately before you set foot in the theater, or even being able to choose from saved notification themes for different contexts. None of these things necessarily require complex algorithms or AI, just better user experience.

Looking to the future.

As we continue down the path of bringing connected technology ever closer to our bodies via wearables and make it ubiquitous in our homes via connected appliances and voice-activated assistants, the way we currently receive notifications will become even more unpalatable. Couple that with a rising awareness of technology addiction and the negative physical and psychological effects of some aspects of our digital lives, and it’s clear that something has to change. I'm not entirely convinced that the idea of notifications is the problem, and that doing away with them entirely is the answer. I believe the issue lies in their ineffective implementation, and the ways in which apps we give permissions to abuse the system. Undoubtedly there are many ways to tackle this issue, but as humans we already have the natural ability to weed out the signal from the noise. Perhaps if technology takes more cues from nature, it will finally speak to us in the language we already understand.

Note: This article was first conceived of as a talk for Interaction 2016, entitled Nature’s Notifications: What Technology Can Learn from a Buzzing Bee and a Thunderclap, which was co-presented with Phillip Tiongson of Potion.

Illustrations by Julia Thummel