The Three Basic Questions Behind Every Content Strategy

Curt Arledge, Former Director of UX Strategy

Article Categories:

Posted on

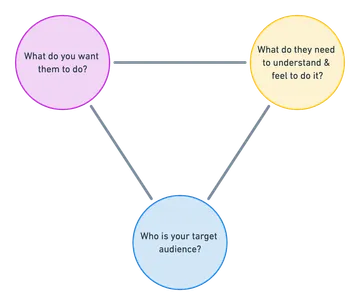

Who is your target audience? What do you want them to do? What do they need to understand and feel to do it?

A business or non-profit organization’s website can play a lot of different roles, but the most important job of a website – besides clearly stating the name of your organization – is often changing people’s minds.

Once a user has landed on your website, chances are there’s something that you’d like them to do, like purchase a product or sign up for an email list. Some users may have arrived with that intention already in mind, but others will require some persuasion.

Does your organization have a coherent theory about how to do this? Many don’t.

Because websites are made out of content, we can think of this “coherent theory” as a content strategy. Your theory of how to change your users’ minds is based on your analysis of the available information, articulated as a strategic plan for what to do about it.

The Three Questions

When I’m working with clients to develop a content strategy, I’ve found it helpful to return frequently to three basic questions:

- Who is your target audience?

- What do you want them to do?

- What do they need to understand and feel to do it?

These aren’t necessarily questions you should be asking stakeholders directly (you can ask, but expect siloed points of view and unproven assumptions). Rather, these are the three questions that I’m trying to answer in the early stages of a project as I’m soaking up as much information as I can from stakeholder interviews, analytics, user research, etc. Each question represents a fundamental, interrelated aspect of a website's content strategy.

Who is your target audience?

In my experience, one of the most undervalued aspects of content strategy is clearly defining a target audience and treating it as an ongoing, testable hypothesis.

Your target audience should be defined and refined based on a steady stream of research insights and data. There is nothing precious or permanent about the audience research you did four years ago. You should be continually forming and (in)validating hypotheses about how your target audiences think, their relative value to your organization, and where there is potential to grow new ones. You should be making time for customer interviews, analytics reviews, and experimentation on an ongoing basis.

The longstanding debate over the value of “personas” as a specific method has obscured the fact that modeling your target audience in one form or another is absolutely essential. It’s a shame that we don’t talk about audience modeling with the same ease and familiarity as content modeling. Audience modeling is all about making informed hypotheses about the most useful ways to group and describe your target audiences. That’s what methods like personas are meant to do: boil down the infinite uniqueness of humans to the most meaningful attributes.

It’s up to you to decide which attributes are the most important to model. It might be any or all of the following:

- Groups served by different product offerings

- Groups with different levels of prior knowledge

- Groups arriving at different entry points or from different sources

- Groups at different stages of the conversion funnel

- Groups whose demographic or psychographic characteristics might have a meaningful impact on how they think and act on your website

The decisions you make about how to model your audience(s) will influence every aspect of your strategy downstream. The more complex and nuanced your model is, the more complex and nuanced your strategy must necessarily be (more on this multiplier effect below). When it comes to audience modeling, rigor is important, but it comes as a tradeoff with simplicity and memorability.

What do you want them to do?

Ultimately, whether you work for a tech startup, a university, a zoo, or a philanthropic institution, your website needs to show a return on investment to justify its cost of existing.

Unless your website exists solely to fulfill some legally mandated obligation, its reason for existing is probably dependent on visitors arriving and doing specific things. These are the conversions that your website exists to facilitate, and for any given website, there is usually a hierarchy of desired conversions and a theory for how visitors can be cultivated to make more and more valuable conversions over time (e.g. reading articles, then signing up for the newsletter, and eventually becoming a paying subscriber). Goals, KPIs, and conversion strategy is beyond the scope of this article, but there are plenty of good resources available out there.

For good reason, information architects are keen to think about websites as kinds of places. It’s less common to think about websites as software, but we should, because in a very real sense, your website is software for creating conversions. (By the way, using this kind of dual metaphor to think about websites is not new.)

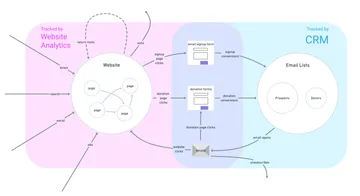

As with any software, you’ll want to know if it’s actually working. Unfortunately, Google Analytics doesn’t come out of the box preconfigured to your conversion goals. It’s also likely that the full picture of your visitors’ journeys towards conversion is distributed across a few siloed systems, like your website analytics and your CRM. Without some kind of integration of these systems, it’s impossible to know whether the content that first pulled visitors to your website actually resulted in conversions some time down the road.

This can get complicated quickly, but it’s not something to leave to the quants and walk away from. Knowing what you want your audience to do – and whether they are doing it – is one of the three basic elements of a content strategy.

What do they need to understand and feel to do it?

What makes someone decide to purchase your product, give you their email address, or donate to your cause? The short answer is, Who knows? People are weird. The longer answer is that these kinds of decisions are based on a mix of logic and emotion.

- Logic: “I have evaluated this product’s attributes and functionality and have decided that it fulfills my needs at a reasonable price.”

- Emotion: “I want to be the type of person who has this product in my home.”

A successful content strategy considers both the findability of needed factual information and the effectiveness of emotional messages that get your audience to “yes.” Some websites might need to lean more heavily on detailed specs, pricing plans, and FAQs. Others might emphasize heartwarming customer stories and inspiring outcomes. Almost every website needs some mix of both.

At best, our websites keep a tenuous hold on our visitors’ attention. People use websites in a hurry. They scan text and click things on impulse. They bring idiosyncratic needs, seeking styles, and prior knowledge.

Our best tools for creating effective content to help our visitors understand and feel what we want them to are information architecture and brand strategy. Information architecture helps your visitors find what they need and provides structures that make things make sense. A brand strategy defines your organization’s personality and style, but more importantly, it defines your value propositions and differentiators. It answers, “What’s in it for me and why should I choose you instead of someone else?”

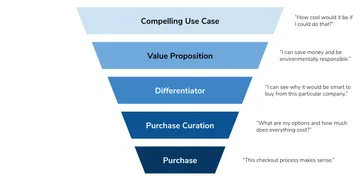

Although you can’t predict or control exactly how a visitor will move through your website, you still need a working theory of how persuasion happens. Your theory of the persuasion journey, which can take the form of a funnel towards conversion, can help you make decisions about how to deploy your content at both the page level and the site level to have the maximum persuasive impact on your visitors.

How they work together

Taken together, these three fundamental questions form a system model of content strategy where each element affects the others. If one element changes (say you’ve added a new target audience or launched a new line of products), you’ll need to reassess the connections between each other element.

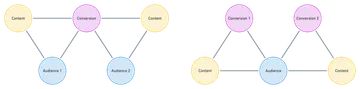

Most organizations have more than one target audience, more than one desired website conversion, etc. It’s important to note that this introduces a multiplier effect that can have a major impact on the size and complexity of the website. For almost all websites, some amount of multiplier effect is unavoidable. You might need to tailor content to address two audiences, or write different content to correspond to different price tiers or giving levels.

Sometimes the multiplier effect is easy to resolve (stick a Careers link in the footer) and sometimes it’s a major implication for scoping content efforts. As a rule, websites tend not to get less complex over time. Non-profit websites seem particularly prone to becoming overstuffed with multiple audiences, conversions, and content over time.

If you should find yourself with two completely non-overlapping target audiences served by two completely non-overlapping product lines, then for all intents and purposes, you’ve got two websites. Even if they share the same domain name and CMS, they’ll need their own content, and again, content is the stuff websites are actually made of.

Conclusion

Who is your target audience? What do you want them to do? What do they need to understand and feel to do it? The answers you define and refine do more than form the foundation of your content strategy – they are your content strategy.

Sure, you might need a snappier, more concise articulation of your strategy to get your team on board and working with shared purpose. But the fact is, you probably won’t be able to reduce the fidelity too much without losing important nuance.

A website is simultaneously a place made of language, software for creating conversions, and a living system, with all of the strange and unexpected things that come along with systems. A sophisticated content strategy should be grounded in a systems-thinking approach and a willingness to theorize, experiment, and refine a model of your target audience, a theory of how you can change their minds through information and emotion, and measurable indicators of your success.