The Power of Divergent Interests

Emmi Laakso, Former Senior Product Designer

Article Categories:

Posted on

Throughout my professional career as a designer, I’ve struggled with guilt. Because while I find user experience fascinating and enjoy the work I do, I don’t devote a lot of time outside of the office to it, and that makes me feel like a fraud.

After all, I come from the generation that lives and breathes “side hustle” culture, that was taught to pursue our passions, to shoot for the moon and, short of that, land among the stars. I also work in the tech industry, which peddles in the language of passion projects and blurs the lines of work and play with hackathons and envy-worthy perks. All of this has made me ask time and time again; shouldn’t I want to doodle user flows at coffee shops for my passion project, or read about the latest tech over my Sunday coffee? If UX isn’t my one true love, am I an impostor?

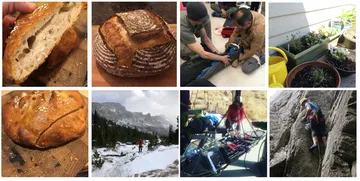

It’s not that I’m lazy. I just devote a lot of time to what I can only call my divergent passions. Among other things, I’ve spent almost a year attempting to make half-decent sourdough (it’s still a work in progress), enthusiastically over-watering my veggie garden, and recently got accepted as a prospective member of the search and rescue group in Boulder, CO and as a result spend many a Wednesday night and weekend morning learning how to predict thunderstorms and carry humans down scree slopes. It would be a stretch to say any of these pastimes directly relate to my job, but as time has gone on, I’ve learned to embrace them as important contributors to my life and my work.

Below: If Instagram is an accurate reflection of my life, all I do is spend lots of time outside and bake bread.

First, divergent activities play an important part in keeping your brain inspired.

“Chance favors the prepared mind.” -Luis Pasteur

If you ask a creative person how they stay inspired, you’re likely to get a whole host of different answers. My partner does his best thinking in the shower. I take long walks. A college friend trawls Pinterest and goes to museums. Whatever the answer, the principles of inspiration are often very similar: they center around an activity that removes the person in question from the problem they’re trying to solve and exposes them to new ideas or a state of flow.

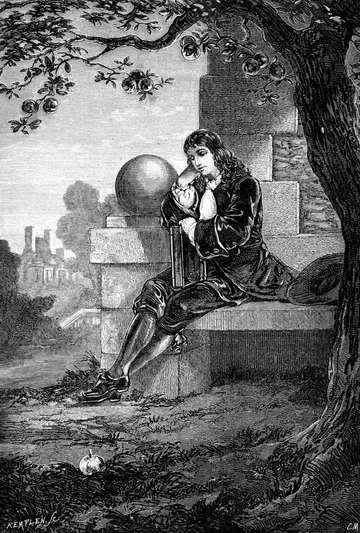

Scientific studies like this one and this one provide an explanation as to why those methods work. When you step away from a creative problem it doesn’t fade away completely; your mind revisits the problem at regular intervals, and as you expose your brain to new information it looks for opportunities to assimilate the new information with the problem at hand. Think of Archimedes stepping into an overflowing bath, or Newton seeing an apple fall from the tree; both scientists’ brains engaged in opportunistic assimilation to solve a nagging problem. Even if your particular problem isn’t likely to be solved by a moment of “Eureka!”, engaging in activities that diverge from the problem you’re trying to solve builds new connections, and getting into a state of flow promotes neuroplasticity. Both of these things help your brain make new leaps between ideas that weren’t connected before.

Below: Newton’s Apple / Alamy Stock Photo

Second, divergent activities teach you transferable skills.

“Hmm! Adventure. Hmmpf! Excitement. A Jedi craves not these things.” -Yoda

Every good Kung Fu movie has a training sequence. And every good training sequence starts the apprentice off doing tasks that have nothing to do with the art of fighting; chopping onions; carrying water; waxing on and waxing off. It’s not until later that the apprentice realizes that they’ve been training the entire time and the seemingly unrelated tasks actually help with hand-eye coordination, strength, and fighting. Movie tropes aside, the idea of transferable skills is hardly a new one. Studies have been conducted to examine the positive impact that participating in sports has on building interpersonal skills and career success, career changing has become common practice, and employers have become more open to employees devoting time to volunteer work and sabbaticals because of the positive returns these have in boosting morale and enhancing problem solving.

Below: The Karate Kid learns to wax on and wax off.

I experienced the power of transferable skills first hand in the summer of 2018, after participating in a month-long mountaineering course designed for outdoor educators. In addition to taking away the requisite skills to cross glacier terrain safely, I left with a newly found respect and passion for the role of effective feedback in creating cohesive teams. Since that experience, I’ve been experimenting with transferring those feedback processes into the office environment with the hopes of recreating the level of trust and camaraderie I found on that trip.

Finally, spending time doing other things helps you keep things in perspective.

“Hooli isn't just about software. Hooli... Hooli is about people. Hooli is about innovative technology that makes a difference, transforming the world as we know it, making the world a better place through minimal message-oriented transport layers." -Silicon Valley

If you have seen Silicon Valley, you might remember a scene where Pied Piper participates in a TechCrunch Disrupt event, and every startup talks about how their solution “X” will make the world a better place. While the show is a satire on the world of technology, the rate at which tech companies talk about “making the world a better place” part is, sadly, all too true. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to improve the world we live in, and I personally believe in the power of technology to do good in specific situations. But working at a company that talks about making the world a better place, or even working in tech, period, isn’t an automatic license to do nothing else to make the world better. As Jennifer Daniels puts it so aptly in her talk called Design is Capitalism, “designers want to change the world, but I just want designers to change San Francisco.” By spending time in participating in a community outside of the tech bubble, we’re reminded that there are many ways to make the world better, even if it’s on an individual or small scale.

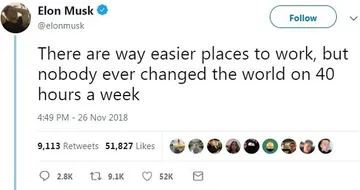

The perspective that comes from spending time doing other things is also a meaningful way to combat the culture of work that has become increasingly accepted in the tech industry among others; the idea that you have to hustle or grind, and spend all of your time doing it, because “nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week” (thanks Elon Musk). Honestly, even if divergent interests don’t inspire you or transfer over to your work in anyway, they still impact your mental health, satisfaction and happiness, which are much more important.

So if you ever, like me, feel guilty about pouring your passion into German melodramatic film, or organic farming, or whatever it is that makes your heart sing, don’t. In my humble opinion, not only do those things ultimately make our work better I believe they also, more importantly, make us into better and happier people. And that’s more than enough to make them worthwhile.