Design Ethics and the Limits of the Ethical Designer

Curt Arledge, Former Director of UX Strategy

Article Category:

Posted on

In our discussions of design ethics, where do designers really fit in?

In the world of design and tech, it's been impossible to miss the flood of content on the topic of “design ethics” over the last year or two. As designers, it feels like discussions of ethics have pervaded every inch of our practice:

Despite the design community’s tendency to create fad cycles (remember when we spent a year arguing about skeuomorphism?), I’ll take this as a positive sign for the maturity of our practice. There are signs that a more conscientious, responsible approach is becoming a stable pillar of our professional identity.

However, the challenge of “design ethics” is that once you start thinking about it, you start to notice it everywhere. It’s not just about the screens we design, it’s about the business models underneath them. And it’s not just about the business models, it’s about the technical and economic structures that enable them. That’s an awful lot of context to keep in mind at once. It reminds me of the Carl Sagan quote, “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”

We see articles and tweets and conference talks about UX dark patterns and accessibility fails. We see stories about frivolous products for privileged people that were probably dreamed up without any designers in the room. And we watch TED talks about big, systemic problems on the Internet and the troubling omnipotence of tech giants like Facebook and Google.

As our discourse about design ethics matures, we need better models for understanding this big, squishy subject so that we’re not talking about everything all at once. What does it really mean to be an ethical designer? What is most important, and what should we care about the most? What power do we really have to make a difference, and how should we use it?

Layered Contexts

One part of the discussion that I think has been missing is an acknowledgement of the nested nature of design decision-making. Sometimes I read popular design articles that blame designers for failures that are way beyond their pay grade, or shame designers into making token gestures that won’t make a dent on the deep, systemic problems. (I won’t name names – you’ll know these when you see them.)

The truth is, most of the decisions that influence a design are made long before designers get involved. In practice, our “design process” is almost always pre-constrained by a mountain of technical and commercial realities.

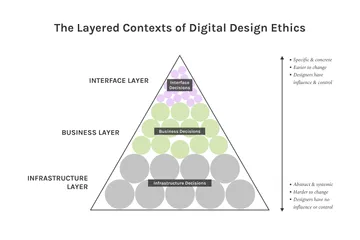

With this in mind, I present the following conceptual model:

In this model, the area of the pyramid itself is the “design decision space.” Every choice that impacts how a digital object works falls somewhere inside this pyramid. Again, many (if not most) of those choices aren’t made by designers. The pyramid is divided into three stacked layers that correspond to the types of design decisions they contain. From bottom to top, the layers are:

- The Infrastructure Layer

- The Business Layer

- The Interface Layer

Starting from the bottom, the decisions in each layer are more influential than the ones above them. The different sizes of circles and the pyramid container illustrate how foundational decisions direct and constrain the possibility space for decisions higher up.

The Infrastructure Layer

At the bottom is what I call the Infrastructure Layer. By infrastructure, I don’t merely mean physical infrastructure like tubes and data centers. This layer refers to the core affordances and limitations of the platform we design and build technology on top of. To a large extent, that platform is the World Wide Web. The architecture of the Web has a cascade of influence on everything we build on top of it.

As Andrew Hinton writes in the wonderful Understanding Context, “The Web is now more a property of human civilization than a platform. It is infrastructure that we treat as if it were nature, like ‘shipping’ or ‘irrigation.’ HTTP could be retired as a network layer tomorrow, but from now on, people will always demand the ability to link to anything they please.”

The infrastructure sits below any single company or its business decisions, but the core design features of the infrastructure incentivize companies to adopt some common business practices, like digital advertising, data collection, and analytics. It’s important to remember that the architecture of the Web could have turned out differently, but this is the version we got.

The Business Layer

As we move up the pyramid, design decisions become specific to individual organizations in the Business Layer. Every organization shares the same infrastructure constraints, but each one follows its own strategy and tactics to survive in the marketplace. The types of decisions that get made in this layer influence the core nature of specific digital objects: what products get made, how they make money, and whom they serve (and don’t serve). Collectively, we can think of these decisions as constituting a company’s business model.

The decisions in this layer are strongly influenced by the company’s core values and leadership. For example, whether a company moves fast and breaks things or moves slow and fixes things translates directly into the moral quality of products a company puts into the world.

The Interface Layer

At the top of the pyramid is the Interface Layer, where we define the concrete interactions between digital objects and their users. These decisions are likely to follow some kind of design process of requirements gathering, research, exploration, refinement, and testing. This is the layer of UX patterns and A/B testing and design sprints and journey maps and a hundred other specialized tools for optimizing software for human use.

As we look at the pyramid from bottom to top, the design decisions go from abstract and systemic to concrete and specific. From decisions that are harder to change to ones that are relatively trivial to change. And from a realm where designers have little or no influence to a realm where designers are in charge.

Though we might not like to admit it, most of us designers are confined to the Interface Layer. In the vast majority of organizations, business-model decisions fall outside of the purview of people with “designer” in their titles. If it seems like this model frames designers as somewhat auxiliary to the rest of the pyramid, that is my intent. This can be a tough pill to swallow, but it’s an important point to make.

I am not trying to let designers off the hook or give you a feeling of helplessness. I just want to be realistic about this hierarchy of decision-making, and make the point that putting ethical digital things into the world is an uphill battle for designers.

So what does this model help us to understand? What can we take away that will actually help us create a more just and accountable digital world? Here are a few possible takeaways.

Infrastructure Is Political

The Web is not well. Our shared information infrastructure has always been morally fraught: we’ve struggled with issues of information quality, bias, privacy, and trust since the Web’s earliest days. Far from being solved, these issues have become supercharged by the consolidation of our infrastructure into the hands of a few giant companies like Google and Facebook. The challenges of the early Web seem quaint in the light of today’s attention economy, mass digital surveillance, weaponized free speech, and the invisible hand of opaque, amoral AI.

This year, Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of the Web, was quoted as saying, “We [have] demonstrated that the Web failed instead of served humanity, as it was supposed to have done, and failed in many places… The increasing centralization of the Web ended up producing—with no deliberate action of the people who designed the platform—a large-scale emergent phenomenon which is anti-human.”

As digital designers, our professional domain is built on top of an infrastructure that has been designed to serve a few giant companies rather than the health of our society, human relationships, and democracy. And as designers, we are pretty much powerless to change it. The design of this infrastructure is a fundamentally political challenge and that we will only solve as citizens, not designers.

In a 2018 Wired cover story, sociologist Zeynep Tufekci (my former professor at UNC, intellectual crush, and one of the best techno-sociology thinkers you will find) reminds us: “In the 20th century, the US passed laws that outlawed lead in paint and gasoline, that defined how much privacy a landlord needs to give his tenants, and that determined how much a phone company can surveil its customers. We can decide how we want to handle digital surveillance, attention-channeling, harassment, data collection, and algorithmic decisionmaking. We just need to start the discussion. Now.”

Designers are in a unique position to help shepherd that discussion. We are systems thinkers, communicators, and we are comfortable with the types of complex trade-offs we’ll need to make to legislate ethical guardrails for our technology. We should all be deeply embarrassed by the technical cluelessness of our elected representatives. It’s our responsibility to pull away from designing screens and “experiences” and lend our skills to the design of policy. It’s infinitely less sexy than the interface, but it’s so much more important.

One other opportunity for designers to influence the infrastructure of the web is through innovation. Disruptive new technologies like decentralized web apps and Tim Berners-Lee’s new project, called Solid, have the potential to upend our Infrastructure Layer. Designers wanting to remake our connected world on a better ethical foundation could do a lot worse than to contribute their time and energy to these innovations. As digital ethicist Tristan Harris says, we need a “design renaissance” to imagine a digital world built for the benefit of the humans who use it.

A Seat at the Table Matters

Most companies are neither absolutely good nor absolutely evil – they’re just making constant tradeoffs about revenue, brand, shareholder value, and somewhere in that mix, either implicitly or explicitly, ethics. This is why the Business Layer is so important, particularly in American society, because regulatory authority is so weak here. Our future will be built from the countless daily decisions made by for-profit companies. Business is at the wheel.

Although 2018 saw a number of high-profile victories for Google employees taking collective action to change corporate policy, this is inherently a reactive approach and arguably an option only available to the privileged. To make truly proactive change from the inside of an organization, designers need more influence over Business Layer decisions.

Designers have been talking about “winning a seat at the table” for so long that it has become a cliché, but this is what we’re talking about: moving down the pyramid from the realm of interface to the realm of business to gain influence over the really important design decisions. It is not enough to ask if something is usable, delightful, or effective; we need to ask if it is good, and we can only do that with deeper influence at the Business Layer.

In his much-read 2018 essay, Design’s Lost Generation, Mike Monteiro admonishes designers for wanting it both ways: gaining decision-making influence while retaining the aesthetic trappings of the aloof, mercurial Designer. The fact is, when you move further down the pyramid, your identity is going to change in ways that might not feel like design. Our industry needs to decide whether we’re satisfied living in a state of arrested development or whether there is a higher calling for our particular set of skills and perspectives.

Part of this higher calling means growing out of an identity based on the reductive philosophy of “Don’t Make Me Think” to a more nuanced understanding of our responsibilities as behavior designers and psychological manipulators. Confining ourselves to a lens of mere usability is a cowardly dodge that has allowed us to ignore our responsibility for too long. We need to make ethics unignorable in the way we teach, talk about, and practice design.

There’s no way for me to tell you how to win that influence, because there are as many different contexts as there are companies. It might mean winning a promotion, or changing job titles, redesigning your own internal processes around staffing and budgeting, or changing the expectations you set with clients. A good place to start might be reading some business books. I’m not going to pretend this will be easy, but we at least need to be clear-eyed about the nature of the challenge.

Conclusion

It seems likely that the biggest challenges for our generation of technologists will be ethical, not technical. Designing responsible digital products requires understanding where we as designers fit in.

An expansive definition of “design” as the accumulation of all the decisions that result in some digital artifact gives designers a more nuanced understanding of the ethical landscape and our place in it. There is much that we can do right now to design more humane interfaces, like following accessibility guidelines, recruiting inclusively for user research, and balancing efficiency with transparency to keep users in control. But we need to bring different approaches to influence the decisions that really matter, beneath the interface in the Infrastructure and Business Layers.

Designers are well equipped to confront thorny ethical problems, but these problems won’t be solved from within our comfort zone at a neatly arranged desk with a cinema display. The true problem solvers among us won’t wait for an invitation to participate.