Being Agile with Agile

Calling yourself "agile" seems to be increasingly important nowadays. However, it's not as easy as following the guidelines for a methodology. Here, explore some pitfalls I've experienced with agile.

We're living in a world of agility. As a computer science student, I was taught that agile is good and waterfall is bad. Coming out of undergrad, it seemed like agile or bust.

In the working world, things aren’t as black and white. No project or team I've ever worked on is purely agile or purely waterfall. It always falls somewhere in the middle and the belief that agile is the only way to achieve success is a bit misguided.

As an example, let's look at scrum, one of the most popular implementations of agile. The creators of scrum have a simple belief – If a project doesn't follow their tenets exactly, it isn't truly scrum. So, for example, in a project where you say “Well, it’s scrum but with X," the project isn't actually scrum. But in practice, blurring the lines a bit isn't a bad thing. I've found being agile with how you and your team define the project’s software methodology leads to far more success than trying to force yourselves to a set of guidelines.

Agile is the methodology of fluidity. It's often used in the form of scrum, where teams focus on “sprints” of developing a feature within a given timeframe, usually 1-2 weeks. They then iterate on this feature set, until the product is finished. Agile excels in handling requirement changes. Based on how the development is separated, it's easy to pivot to working on a new subset of features in the next sprint without having to waste much time.

That said, it isn’t invulnerable to the problems associated with requirement changes. Some of the worst headaches I’ve had are when the client changes requirements mid-sprint. This is just something that should not happen, which is why it's imperative to make sure the feature sets for each sprint is agreed upon before the sprint begins. That is the purpose of many of the other sprint “ceremonies,” like backlog refinement (where the team combs through the backlog of tasks, takes notes where clarification is needed, and even assesses difficulty) and sprint planning (going through the backlog, likely with the client, to see which tasks/stories will be taken on in the workload of the sprint).

Agile/scrum is meant to be cyclic. Implementing software in one area of the product shouldn't be held back by needs from another area. The team can focus on a subset of features for the sprint and handle all of the requirements needed for gathering, designing, and implementation.

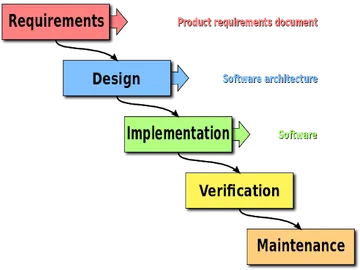

Waterfall, by contrast, is characterized by being very linear. The product is broken down into various steps, such as “gathering requirements,” “design,” “implementation,” and “maintenance” to name a few. Rather than working through these four steps every iteration, each step should be completed before the next can start. This is where the image of a waterfall comes into play.

Before I came to Viget, I worked on a team that acted as the agile guinea pig for our client – they wanted to experiment with agile but had no real understanding of what it meant in practice. So that's where we came in. Our team was tasked with not only developing the product but teaching the client about how agile works. This allowed us to see the problems that come with agile development, and we learned some important lessons I've shared below.

Everyone involved needs to buy into the methodology used

This is not unique to agile, however; if teammates aren't on the same page for the structure of the product, there will be friction. Friction slows down the development process and can lead to falling short of the goals for the sprint, which ultimately leads to more friction at the end-of-sprint ceremonies. As you can imagine, this has the possibility of creating a nasty feedback loop of unhappy clients.

At my last job, it took a couple of sprints for the stakeholders on the client’s side to understand that the demo we provided was a subset of features. We did not complete the entire 16-month project in two weeks, much to their dismay. The slot of time we had for the demo was an hour-long. It ended up being over two hours in total. If I’m remembering correctly, most of that time was spent asking about features that weren’t even close to being in the scope of that sprint. This was frustrating, but eventually, it got smoothed out once everyone bought into and set their expectations for an agile product.

If a specific ceremony or feature of a methodology is not working for your team, it is fine to drop it.

While it may disqualify you from being pure “scrum,” picking and choosing what to use from a software development methodology is not a bad thing. It can be used as a way to negotiate among team members and clients and get rid of friction much more easily than forcing one party to adapt. For example, we tried multiple times to facilitate a “scrum master” role in our team. A scrum master is a team member meant to be a liaison between the team members, client, and scrum method as a whole. Ideally, this would be an employee's full-time job on the project, rather than a secondary set of responsibilities. The actual duties of a scrum master can vary between projects, but for our purposes, we wanted a scrum master to be running the ceremonies and act as a bridge between the developers and the stakeholders.

Alas, this ultimately did not work for us. We found much more success by dropping that role and having a more direct line of communication between all parties. In addition, we agreed to rotate who ran each ceremony, so that everyone could get experience.

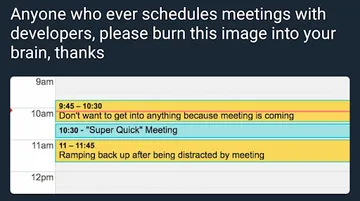

Agile can lead to far too many meetings

One of the biggest challenges we faced was balancing the huge number of meetings we had with making sure we have time for development. This picture I got from Twitter is a perfect example of the problem:

Developers should be involved in meetings, even if it detracts from development. The main problem is when there are multiple meetings in a large block of time, like the entire afternoon. Even if they aren’t scheduled back-to-back, context-switching between being development-focused and meeting-focused takes a very long time. We had entire afternoons eaten up by just three meetings that were poorly timed.

We struggled with balancing meetings and development often, partly because of everyone having a share of scrum master responsibilities, but mostly because of massive scope creep. The more scope creep we had, the more meetings were required to verify we had properly addressed the scope creep, and the less time we had for development.

Scope creep

Ah, my favorite concept. Scope creep is when the agreed-upon scope of the work is shifted. This can be benign, with the client thinking mid-sprint to add something like a small tooltip to some form field. Unfortunately, some scope creep can seem benign and result in a huge lift.

Scope creep is probably as fun for project managers as it is for developers. At Viget, I have been lucky enough that the project managers here are incredibly skilled at stopping creep before it reaches developers. This isn't always the case. For example, if there are shared responsibilities for managing the backlog and the developer doesn't explicitly push back, scope creep can worm its way in. Scope creep also leads to a negative feedback loop. If you comply and incorporate a new feature that was out-of-scope, then the client starts to think this is how the project workflow works. This gets incredibly dangerous when the feature creeping its way in is not trivial. Avoid agreeing to trivial scope creep where you can, so that you can avoid having to have an awkward conversation down the road involving something like “Oh, but you did this for me the last sprint with feature X...why can’t you do it for this feature too?”

One of the things I like about Viget is that we are not set in our methodologies. Some projects have more agile components, some are more waterfall. They vary based on what that project needs, as well as input from team members and clients. When I was first interviewing for jobs out of undergrad, one of the main questions I would ask the company is “do you practice agile?” Most places would say yes, but for those that gave a more complicated answer, I would instantly feel a little uneasy. However, after starting my career struggling to be perfectly agile, I welcomed the complex answer that Viget gave when I asked the question. They did not fall into any specific category of software development methodology.

Each project had its own requirements for what they needed, based on team size, client type, and project length. If you are struggling with similar problems that I mentioned above, consider diving deeper into your process as a whole. It's okay to change up your process. Do what makes sense for your team, rather than what you learned in a textbook. Agile has some great ideas, but so does waterfall. I now believe the most successful approach to software development is to be agile with how you use agile.