A Foundations-First Approach to Product Design

Today’s consumers expect greatness when it comes to the products they use. To get there, start with the basics.

At Viget, our product design team has the unique opportunity to see a wide variety of products and services come through our doors. On a daily basis we might be building a clickable prototype in Figma to test an idea, collaborating with a new entrepreneur to launch an MVP, or consulting with a client to rethink an existing product or feature.

The diversity of work means that each project requires us to quickly get up to speed on the industry, work with new stakeholders, and solve new problems through strategic thinking and design.

For new product designers, getting started can be intimidating. It’s easy to fall into the trap of feeling like you need to have all the answers, but the reality is, you don’t know what you don’t know.

Rather than jumping straight into high-fidelity mockups, take a step back to consider a baseline strategy. In short, you’ll want to better understand the Who, Why, What and How to inform your decisions and align stakeholder decision making. For larger projects that require in-depth knowledge this process could be more extensive, whereas for small, fast-moving projects it might be less intensive. The key to success here is that no matter how much time, resources, or budget you have, the following questions deserve answers.

Who are you designing for?

Understanding who you are designing for is critical in determining what features are prioritized, how design decisions are made, and inevitably what product gets built.

It’s important to identify and further understand the intended audience, which may be presumed rather than documented. As a designer, your understanding of who the product is being built for will be your best weapon for articulating design decisions and aligning on project outcomes. You should dig into the user’s core attitudes, behaviors, and emotional drivers.

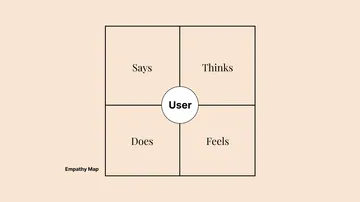

Depending on the project, mapping the customer experience can help empathize with your users and further understand how their behaviors may influence the way they interact with the end product.

No matter what approach you take, be careful not to reinforce biases. Your “users” are people who live in an ever-changing world and have moods, attitudes and feelings that frequently change. A well-rounded understanding of your users allows your design to accommodate their complex needs – rather than being limited by them.

Why should the product exist?

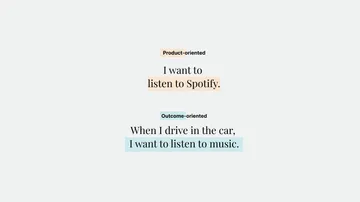

Once you understand who your users are, you can start thinking about the real world problems they need solved. For example, a person might want to listen to music, so they open Spotify. The underlying need is the desire to listen to music, not to use Spotify. By taking an outcome-oriented approach at this stage in the process, you can avoid producing short-sighted solutions that may not take into consideration the entirety of the experience.

For some clients, the users’ “Why” can be expressed in a sentence or two right off the bat, but for more complex industries or products, it can be more convoluted or require more time to uncover.

Our product designers and strategists have day-long workshops and weeks devoted to articulating the “why” because a.) it’s that important and b.) it’s that important.

If you’re looking for a place to start, the jobs to be done framework can be a helpful first step in beginning to define customer needs by focusing on the intended outcomes of the product rather than getting tied up in expected features.

What are you building?

Once you understand the underlying needs of the user and why the product should exist, you can begin defining “What” the product will do to address the need. It’s at this point where we can review existing solutions, revisit proposed ones, or even begin forming our own hypothesis.

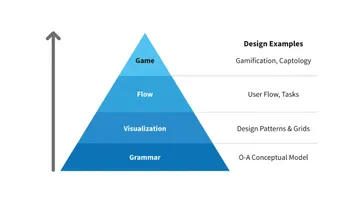

Start with the fundamental building blocks of the product, then work your way up to more tangible artifacts. This helps create a cohesive, effective, and pragmatic user experience. In the semantic approach for example, this means defining the underlying grammar and taxonomy, then identifying high-level user flows, page archetypes, and patterns.

Determining what the product will be or how it will function can look very different depending on the designer, what type of work you need to get done, and how long you have for the process. Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for this process.

The key is to not limit your creativity in this phase, and instead think of the big picture in order to solidify the conceptual model. You’ll need to ensure it not only solves the problem, but aligns with how the user thinks it will work. That’s not to say you will build everything you dream up, but inversely, you don’t want to ignore the potential in favor of the realistic.

How will you build it?

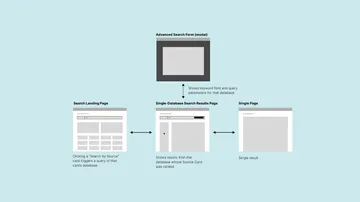

The last piece in this somewhat oversimplified puzzle is determining how the solution will be brought to life and how it will be differentiated from other solutions in the market. For this phase, you will need to align on how to — literally — do the work.

Visual artifacts such as a site map of the product, flow diagrams or low-fi wireframes can help project managers, engineers, and stakeholders align on the vision and support budgeting and implementation strategies.

Just remember that while you might have a grand vision, the state of the product and your client’s goals, capabilities, budget, timeline, and roadmap will ultimately determine what your focus should be.

Don’t stop asking questions

Understanding the Who, Why, What and How is crucial to forming a unique perspective on the product and can set the project up for long-term success by creating cross-team alignment, ensuring technical feasibility, and leading to a more effective user experience.

That being said, don’t get too comfortable. These questions should always be top of mind. As your product changes, so does your understanding of the landscape. Referring back to this knowledge and expanding on it ensures your solutions are thoughtful, comprehensive and solving the right problems at the right time.